|

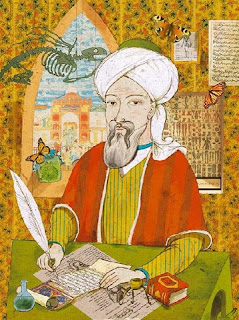

| Avicenna - father of modern medicine |

The Arabs could measure the earth’s circumference (a feat not matched in the West for eight hundred years), they discovered algebra, were adept at astronomy and navigation, developed the astrolabe, and translated all the Greek scientific and philosophical texts.

Of particular interest to travellers to Uzbekistan are Avicenna (the Latinized name of Ibn Sina) and Al-Khorezmi.

Avicenna was born in 980 A.D. in the village of Afshana near Bukhara. He was clearly a precocious youth: aged 10 he knew the Koran by heart, before he was 16 he had mastered physics, mathematics, logic, and metaphysics, and at 16 he began the study and practice of medicine. By the age of18 he had built up a reputation as a physician and was summoned to attend the Samani ruler Nuh ibn Mansur, who, in gratitude for Avicenna’s services, allowed him to make free use of the royal library, which contained many rare and even unique books.

In 1025 Avicenna completed the encyclopedic Canon of Medicine, one of the most famous books in medical history. After translation into Latin in the 12th century, it became the textbook for medical education in Europe and Asia for the next 600 years. Among the Canon's contributions to modern medicine was the recognition that tuberculosis is contagious, diseases can spread through water and soil and a person's emotional health influences his or her physical health. Avicenna was also the first physician to describe meningitis, parts of the eye, and the heart valves, and he found that nerves were responsible for perceived muscle pain. Avicenna, the most famous and influential polymath of the Islamic Golden Age, died in 1038.

|

| Al-Khorezmi's statue, Khiva; image: G. Menon |

Al-Khorezmi made major contributions to the fields of algebra, trigonometry, astronomy, geography and cartography. He wrote more than 20 research works, the most famous of which is the Concise Book of Calculus in Algebra. This work was extremely influential: European thinkers corrupted the word 'al gabr' (calculation) to algebra and Al-Khorezmi's name to 'algorithm', naming the mathematical concept after him.

His other major contribution to mathematics was his strong advocacy of the Hindu numerical system, which he recognized as having the power and efficiency needed to revolutionize mathematics. The Hindu numerals 1 - 9 and 0 were soon adopted by the entire Islamic world and later, Europe.

In addition to his work in mathematics, Al-Khorezmi made important contributions to astronomy, also largely based on methods from India, and he developed the first quadrant (an instrument used to determine time by observations of the sun or stars), the second most widely used astronomical instrument during the Middle Ages after the astrolabe. He also produced a revised and completed version of Ptolemy's Geography, consisting of a list of 2,402 coordinates of cities throughout the known world.

To throw in two other names: the great scientist Al Biruni - also from Khorezm in present-day Uzbekistan. He pioneered the notion that the speed of light was much greater than the speed of sound, observed solar and lunar eclipses, and accepted the theory that the earth rotated on an axis long before anyone else.

Ahmad Ferghani, from the Ferghana Valley, was an astronomer, mathematician and geographer. His main work was the Book of Celestial Movements and a Code of the Science of Stars. He identified the dates of the longest and shortest days of the year and advanced the theory that the world was round.

These men were profound thinkers who advanced the frontiers of knowledge. Why are their names and contributions so little known today in the West? It is this issue that Jonathan Lyons explores in his book. If it's a topic that interests you too, you would certainly enjoy this Library of Congress webcast of Jonathan Lyons' lecture. Settle down with a cup of tea -- it's 56 minutes and well worth the investment.

Related posts:

Omar Khayyam in Samarkand and Bukhara

Travelling the Great Silk Road to Canberra, Australia

Arminius Vámbéry : a Dervish Spy in Central Asia

Mennonites in Khiva 1880 -1935

Langston Hughes: An African American Writer in Central Asia in the 1930s