|

| Yosif Stalin Roane's parents, Jospeh and Sadie |

Yosif Stalin stood before his Kremlin, Virginia USA, home on a windswept, spring afternoon, his weathered hands gripping his walker. "I still own it," he said of the white, two-story house off a lonely country road.

It's no coincidence that this octogenarian was named after one of the 20th century's bloodiest dictators, but it's just half of his name. His full name is Yosif Stalin Kim Roane, and he was the first child of African-American parents ever born in the Soviet Union.

"Didn't nobody pay that no mind," Roane said of his notorious namesake in a recent interview with RFE/RL. "They mostly called me Joe."

Roane, 84, is among the few living offspring of African-Americans who traveled to the Soviet Union in the 1920s and 1930s to seek a better life in the nascent communist state. Most of these voyagers were driven by political convictions or economic hardship amid the Great Depression and pernicious racism in the United States, including the segregationist Jim Crow laws of the American South.

That Roane was born in an empire run from the Kremlin and grew up in this tiny Virginia hamlet of the same name is a coincidence that inspired the title of a recent documentary, Kremlin To Kremlin, aimed at preserving the record of his family's remarkable journey for future generations.

|

| Yosif Stalin Kim Roane at the exhibtion in Kremlin, USA |

The elder Roane, who died in 1995, is widely credited with helping develop a successful hybrid of American and local cotton capable of growing more quickly in Uzbekistan. "Of course Uzbeks knew cotton growing, but these new types of cotton dealt big changes in the industry," Bekjon Toshmuhammedov, a biology professor from Uzbekistan, tells RFE/RL's Uzbek Service. "As far as I know, Uzbeks still grow the types of cotton created by the Americans."

Raised in a well-to-do African-American family in Kremlin, Virginia USA, Joseph J. Roane studied agronomy in college. After graduating, he was recruited to come to the Soviet Union by Oliver Golden, a black cotton specialist from Mississippi who would ultimately give up his U.S. citizenship and remain a Soviet national until his death in 1940.

Golden had been a student of the renowned African-American agricultural scientist and inventor George Washington Carver, who helped select the team of agronomists. Soviet authorities had seized on the plight of black Americans as an antipode to what they promoted as their new classless society free from racism. Indeed, many of the dozens of African-Americans who relocated to the Soviet Union praised the way they were treated there, even as more and more Soviet citizens were being targeted in the snowballing Stalinist purges.

|

| Agronomist George Tynes flanked by Soviet army cadets |

These travelers came in various groups. In addition to the agronomists recruited by Golden, one group that was brought over to make a Soviet propaganda film about the evils of racism included the influential Harlem Renaissance poet Langston Hughes.

The film never materialized, though Hughes traveled through the Soviet Union and met Golden and the elder Roane in Uzbekistan.

"Then you have some political trainees from the 1920s who were very attracted to this country that professed a nonracial society and actually treated them in a hospitable way that was totally unheard of in the United States," Joy Gleason Carew, author of Blacks, Reds, And Russians: Sojourners In Search Of The Soviet Promise, tells RFE/RL.

"It's amazing when you think about these people willing to leave home, and country, and language, culture for what they hoped would be a better life," adds Carew, an associate professor at the University of Louisville, in Kentucky.

Both Golden and his wife, a Polish-Jewish American named Bertha Beliak, were committed communists. Golden found work as a scientific researcher at Tashkent’s Irrigation Institute and was elected to local political office, opportunities he would have been denied in the U.S.

But the elder Roane said later that he "hardly knew where the Soviet Union was when Golden came to my college to speak" and that that he didn't know "exactly what a communist was."

|

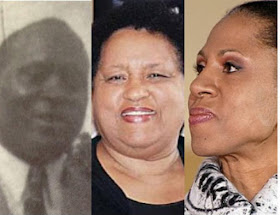

| Left to right: Oliver Golden, his wife Bertha Beliak and daughter Yelena Khanga |

"Secondly, I was young and I wanted to see the world. I thought this might be the only chance I'd ever get," Khanga quotes him as saying in her 1992 book about growing up as a black Russian-American.

Roane and his new bride, Sadie, decided to make a honeymoon out of the trip. The group of agriculture specialists arrived in Leningrad in November 1931 after a four-week journey and then traveled to Uzbekistan, where they found ramshackle housing and infrastructure.

But they received better wages and accommodation than the locals. "The Soviets did make extra overtures to them to make sure they were a little more comfortably housed than the average Uzbek," Carew says. This hospitality was evident when Sadie Roane gave birth to Yosif in Uzbekistan's capital, Tashkent, on December 4, 1931. "She had at least five nurses to help her take care of me," Yosif says. "She had all kinds of help, as if she was a celebrity."

Much of what Yosif recounts about the Roanes' life in Soviet Uzbekistan is based on hearsay because of his young age at the time. But he says that he remembers meeting other prominent African-Americans who visited the country. These include the famed performer and civil-rights activist Paul Robeson, who came under withering criticism at home for his vocal admiration for Stalin and the Soviet state. "Paul Robeson carried me around on his shoulders," Yosif says.

Watch a 2-minute clip of this fascinating story. [ If this clip does not appear on your device, please go directly to https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B52bNZqTynA ]

Stay tuned for the 2nd part of this extraordinary slice of history.

>

Related posts:

Langston Hughes: An African American Writer in Central Asia in the 1930s

Remembering Muhammad Ali’s Visit To Uzbekistan

Sidney Jackson - An American Boxer in Uzbekistan

This article is republished with permission. Copyright (c) 2017. RFE/RL, Inc. Reprinted with the permission of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, 1201 Connecticut Ave NW, Ste 400, Washington DC 20036.